Recently, the Deschutes River Alliance officially opposed Pelton Round Butte Hydroelectric Project’s (PRB) Low Impact recertification by the Low Impact Hydropower Institute (LIHI).

DRA objected to the low-impact recertification because PRB fails to comply with water quality and threatened and endangered species protection. Failure to comply with either of these criteria alone is enough to prevent recertification. In addition to these shortcomings, there are serious concerns that PRB’s operation results in significant methane emissions. Before certifying the PRB Project as low impact, LIHI must ensure that the facility is not emitting these potent greenhouse gasses and negatively impacting global warming. Considering these shortcomings, we oppose any action to recertify PRB as a low-impact facility.

The certification is awarded and managed by LIHI, a non-profit organization that was started in 1999. LIHI’s stated purpose is to set criteria and conduct a program to certify hydropower facilities that are low-impact, and make information about the impacts of hydropower available to the public. LIHI certifies hydroelectric facilities across the county and annual fees and application fees from the hydropower companies are the primary income sources for LIHI.

Certificate term ranges from 10 to 15 years and during that time, the facility is also subject to annual compliance reviews, mid-term reviews in some cases, and a recertification review at the end of the certificate term. The previous certification was influenced by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, public-funded state agencies whose purpose is to protect water quality and aquatic life. Despite the declining water quality in the lower Deschutes River and the ongoing threats to trout, steelhead, and salmon, DRA is not expecting any objection by DEQ or ODFW and the recertification will likely be approved.

Criteria

The Certified Low Impact hydropower projects or facilities must meet eight specific science-based environmental, cultural, and recreational criteria established by the LIHI:

1) Ecological flow regimes that support healthy habitats – Goal: Flow regimes in riverine reaches that are affected by the facility support habitat and other conditions suitable for healthy fish and wildlife resources

2) Water quality supportive of fish and wildlife resources and human use – Goal: Water quality is protected in water bodies directly affected by the facility, including downstream reaches, bypassed reaches, and impoundments above dams and diversions

3) Safe, timely and effective upstream fish passage – Goal: Safe, timely and effective upstream passage of migratory fish so that they can successfully complete their life cycles and maintain healthy populations in areas affected by the facility.

4) Safe, timely and effective downstream fish passage – Goal: Safe, timely and effective downstream passage of migratory fish. For riverine (resident) fish, the facility minimizes loss of fish from reservoirs and upstream river reaches affected by facility operations. Migratory species can successfully complete their life cycles and maintain healthy populations in the areas affected by the facility.

5) Protection, mitigation and enhancement of the soils, vegetation, and ecosystem functions in the watershed – Goal: Sufficient action has been taken to protect, mitigate and enhance the condition of soils, vegetation and ecosystem functions on shoreline and watershed lands associated with the facility.

6) Protection of threatened and endangered species – Goal: The facility does not negatively impact federal or state listed species. Facilities shall not have caused or contributed in a demonstrable way to the extirpation of a listed species. However, a facility that is making significant efforts to reintroduce an extirpated species may pass this criterion.

7) Protection of impacts on cultural and historic resources – Goal: The facility does not unnecessarily impact cultural or historic resources that are associated with the facility’s lands and waters, including resources important to local indigenous populations, such as Native Americans.

8) Recreation access is provided without fee or charge – Goal: Recreation activities on lands and waters controlled by the facility are accommodated and the facility provides recreational access to its associated land and waters without fee or charge.

Water quality and endangered species issues

The clearest instance of the significant impacts stemming from PRB operations is the water quality. The stated goal is to ensure water quality is protected in water bodies directly affected by the facility, which includes downstream waters. The standard further clarifies that if any water body affected by the facility has been defined as being water quality limited … the applicant must demonstrate that the facility has not contributed to the impairment in that water body. The lower Deschutes River temperatures are warmer both overall and for a longer period of time, dissolved oxygen (DO) levels do not support native fish’s biological needs, and the river’s pH levels exceed basin standards.

This decline in water quality is directly attributable to the installation and operation of the Selective Water Withdrawal (SWW) tower at Round Butte Dam. After more than a decade of operations and attempted adaptive management to avoid making minor changes to improve water quality, the PRB is not a Low Impact facility and it is unclear if the SWW tower will ever be able to meet the conditions promised by the operators when the project was relicensed to generate power.

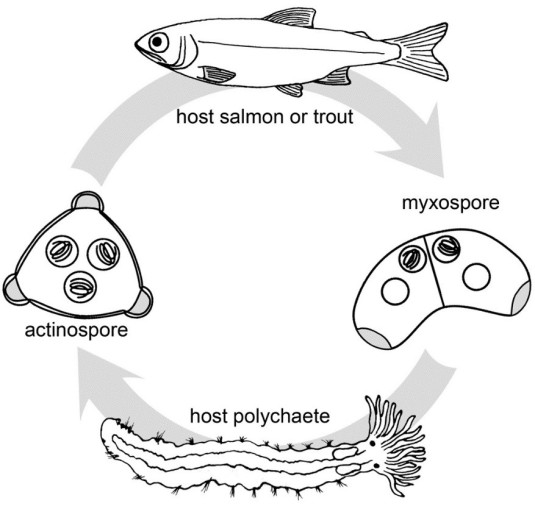

PRB’s negative impact to threatened and endangered species has roots back to when the dam was built and blocked off hundreds of miles of historically-used spawning and rearing grounds. Although the SWW tower installation was designed to improve opportunities for the currently listed bull trout and steelhead below and above PRB, the decline in water quality, and more than a decade of reintroduction efforts for these fish, as well as salmon species, the runs have essentially remained stagnant and far below sustainable, self-supporting, or harvestable runs. As a result, LIHI cannot recertify Pelton Round Butte as a Low Impact facility.

Methane emissions behind dams

Emerging science is bringing a new impact of hydroelectric dam operations to the attention of operators, regulators, and conservationists – methane emissions. Research out of Washington State University shows that hydropower reservoirs are a major source of human-caused methane emissions. Studies of dams in Oregon and Washington have found that reservoirs with high chlorophyll-a levels have heightened methane production and are likely to have significant methane emissions.

Globally, reservoir-originating methane emissions are a top-6 source of methane – on par with biomass and biofuel burning or global rice cultivation. PRB’s reservoirs seem to fit the necessary conditions to be considered a significant emitter of methane. Its two largest reservoirs – Lake Billy Chinook and Lake Simtustus have such high chlorophyll-a levels that they are listed as impaired in a DEQ report submitted to the EPA. While this emerging issue and its impacts do not neatly fit neatly into any current review criteria, LIHI should seriously consider the resulting impacts from methane emissions before facilities like PRB receive a low-impact certification.

Collectively, these issues would seriously call into question any low-impact certification for the PRB and we encouraged LIHI to reject the recertification of the Pelton Round Butte Hydroelectric Project as a Low Impact Facility.

You can read our letter here – https://lowimpacthydro.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Deschutes-River-Alliance-Comment-Letter-Pelton-Round-Butte-Recertification-Application-2023.pdf

You can learn about The Pelton Round Butte’s Low Impact recertification here https://lowimpacthydro.org/lihi-certificate-25-pelton-round-butte-project-oregon/

You can learn more about LIHI here https://lowimpacthydro.org/

Deschutes River Alliance: Cooler, cleaner H2O for the lower Deschutes River.

Click here to Donate.

Click here to sign up for the Deschutes River Alliance email newsletter.